My roots are Latvian, with life leading me to London. I needed a place to begin, and Jāzeps Grosvalds’s story became that starting point- an inspiring one. His life- at once cosmopolitan and deeply rooted in Latvian identity- resonates in unexpected ways. Through these stories, I hope to share more about Latvian heritage.

Jāzeps was born on April 24, 1891, in Riga, as the fourth child in the family of Fridrich and Marija Grosvalds. His father, the son of a miller, had earned a law degree from the University of St. Petersburg. A prominent lawyer, he served as the head of the Latvian Society from 1885 onward. Fridrich Grosvalds possessed a unique diplomatic talent, which he also passed on to his children.

In the family’s elegant Riga apartment, members of the city’s social elite would regularly gather- high-ranking officials, influential merchants and industrialists, writers, artists, and actors.

In 1902, Grosvalds hosted a banquet at which his friend, the well-known painter Janis Rozentals, met the love of his life- the Finnish singer Elli Forssell. It was Rozentals who first noticed Jāzeps’s artistic talent and drew his parents’ attention to their son’s remarkable gift.

Jāzeps Grosvalds was raised with an unusually free spirit for his time- no expectations were placed on him regarding education or a future profession. His parents supported his dedication to art, as their ambitions for a professional career were already fulfilled by their elder son, Olģerds. The examples set by prominent Latvian painters of the time, Vilhelms Purvītis and Jānis Rozentāls, also played a role- demonstrating that artists could be both wealthy and respected in society.

Jāzeps was an excellent pianist, a voracious reader, and fluent in German, English, French, Russian, and Latvian. He adored Oscar Wilde- his provocative elegance and the mysterious green carnation in his buttonhole. His parents gladly ordered luxurious art books and magazines for him. The young Grosvalds admired Aubrey Beardsley’s illustrations for Wilde’s plays. He even created his own books and magazines- carefully selecting typefaces, drawing vignettes, and illustrating them himself.

Together with his parents, Jāzeps travelled across Europe, keeping journals in different languages- choosing the one he felt best captured the essence of his experiences in each country. Friends and family called him “Joe.” His older sister, Mērija, who was passionate about Latvian ethnography, married Lutheran pastor Jānis Grīnbergs in 1907. He led the Lutheran congregation in St. Petersburg, and Jāzeps spent almost every Easter with their family. They would stroll through the Summer Garden and visit the Hermitage.

In 1913, Jāzeps painted a portrait of his five-year-old niece, also named Mērija, a work that delighted her parents. Through the pastor’s connections, he was granted a meeting with the influential artist Konstantin Somov, a member of Mir iskusstva (“World of Art”), an influential Russian art movement. Jāzeps showed him his drawings, and Somov praised the young man’s talent, encouraging him to pursue painting more seriously.

At the time, it seemed to everyone- both in Riga and across Europe- that a wonderful new era had begun. Riga was flourishing: the first trams and automobiles appeared on the streets, and electric lights began to glow in homes. After finishing gymnasium, Jāzeps was allowed by his father to go to Munich- on the condition that he travel with his older brother, who had promised to support him and pay for his art classes.

Jāzeps was passionate about gymnastics, tennis, horseback riding, ice skating, and skiing. He was an excellent dancer and popular with girls. In Munich, he embraced a bohemian lifestyle, frequently visiting cabarets and theaters. He studied at the studio of Hungarian artist Simon Hollósy, whose work combined elements of Post-Impressionism and Modernism.

Comparing himself with other artists, Jāzeps realized he lacked academic training- particularly in anatomy and drawing technique. This realization deeply troubled him.

Of course, Jāzeps could have enrolled in an academic art school- but that would have required serious effort, and he was used to things coming easily. The need to earn a living often motivates artists to improve, but Jāzeps had no such pressure. He didn’t need to paint in order to sell his work; he could afford to do it for the joy of it, or for the sake of an idea.

When he turned to his father for advice, he received a brief reply: “Just draw!”

So, the young man once again set off on a tour of Europe’s finest museums. Inspired by what he saw, Jāzeps made the resolution to work hard- and promptly enrolled in a tango school in Munich.

There, he found himself among a crowd of young, provocative, wealthy individuals hungry for public pleasures. He paired off with a couple of carefree girlfriends, and together they frequented dance halls- forgetting all about anatomy and academic drawing.

After his time in Munich, Jāzeps returned to Latvia to complete his military service in a cavalry regiment. Once finished, he declared to his parents: “Now I am ready to devote my life to art!”

And the best place to live for art, of course, was Paris. So, his father once again gave him the funds he needed, and Jāzeps set off- this time alone- for the French capital.

On his first day in Paris, he rode in a carriage past the Tuileries Garden, overcome by a sense of freedom. That evening, he wrote in his journal: “I cried at the thought that I might one day have to leave this place.” The atmosphere of Paris intoxicated him.

From then on, no matter where he went, he always carried a sketchbook. He received permission to copy works at the Louvre, painted scenes from the view outside his window, and made costume sketches, which he compiled into handmade journals and sent to his youngest sister.

Jāzeps returned to Riga in 1914 and joined the Latvian Art Promotion Society. That same year, he exhibited his work at the fourth Latvian Art Exhibition. He quickly formed friendships with young artists such as Konrāds Ubāns, Voldemārs Tone, and Kārlis Johansons. Together they formed a group of emerging modernists, adopting a name coined by Jāzeps himself- “Zaļā Puķe” (“The Green Flower”). Later, the artists Romans Suta and his wife Aleksandra Beļcova also joined the circle.

Jāzeps was charismatic and well-connected. He was familiar with all the latest trends in modern art, had seen many classical masterpieces firsthand, and kept up with developments in the international art world. The group planned to hold exhibitions, stage plays, publish books… but those plans were soon disrupted by the war.

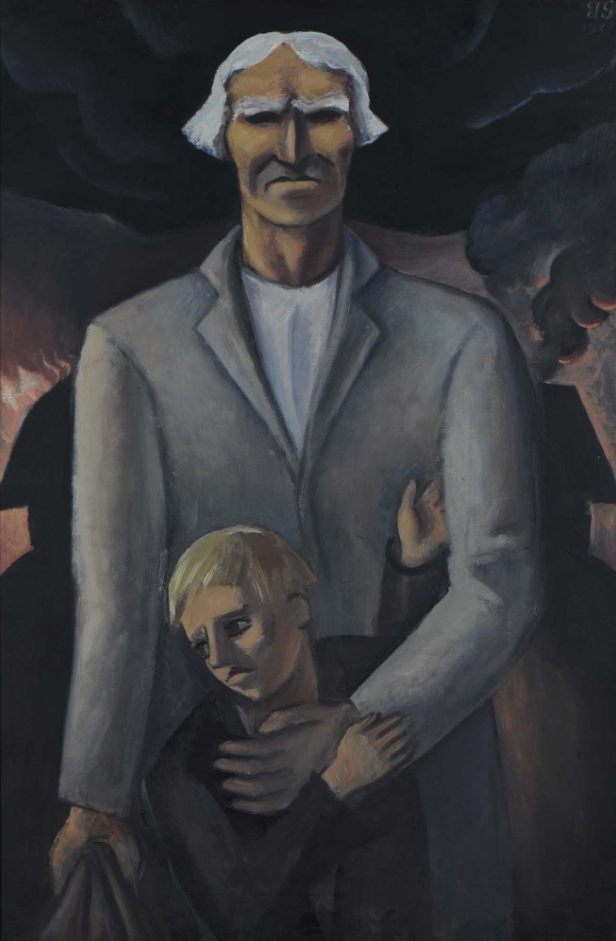

From the very first days of World War I, Jāzeps’s mother was active in supporting reservists and refugee families, and Jāzeps joined her efforts. He witnessed families displaced from their homes, elderly people and children who had lost everything, heading into an uncertain future. For someone who had lived his whole life in a safe, beautiful, and privileged world, it was a profound shock.

Driven by these impressions, he felt compelled to paint what he saw. The experiences awakened in Jāzeps a deep sense of his true talent as a painter. He no longer worried about lacking classical academic training. Instead, he began seeking new and unconventional means of artistic expression.

His style evolved towards neoclassical modernism, marked by a restrained and elegant colour palette. Rather than painting peasants in idyllic rural settings, Grosvalds used photographs from ethnographic expeditions as his source material. In these references, all the faces were photographed frontally, to clearly show the characteristic features of different regions. Grosvalds adopted the same approach- his portraits were always full-face, not of specific individuals but stylised, generalised representations of the Latvian people.

His paintings on the theme of refugees are now part of the Golden Canon of Latvian art.

Jāzeps’s parents could no longer provide their children with the comfortable lifestyle they had once enjoyed. His older sister began teaching foreign languages, while his elder brother secured a position in the diplomatic service.

In 1915, Jāzeps volunteered for military service and was assigned to the 6th Tukums Latvian Riflemen Regiment, where he was appointed commander of the cavalry unit. Eager to prove himself as a soldier, he had even planned to paint scenes from the battlefield.

But the war had changed- it had become a static trench war. Now, a man could be killed by a shell without ever seeing his enemy. In his letters, Jāzeps often wrote simply: “At the front- no changes”

During quiet moments, he sketched the trenches and dugouts in pencil.

In 1916, thanks to his linguistic abilities and talent for getting along with people, Jāzeps was transferred to Petrograd (now St. Petersburg), where he was given a post that was almost diplomatic in nature. When Allied delegations arrived, he acted as their guide around the city- taking them to restaurants, the theatre, official meetings, and diplomatic receptions.

After the Bolshevik Revolution, Jāzeps went to England, becoming one of the so-called “ownerless” officers of the Tsar’s army. The British had created a separate expeditionary corps for them, and the choice was simple- either enlist or leave. Without citizenship, there was no real alternative, so Jāzeps joined.

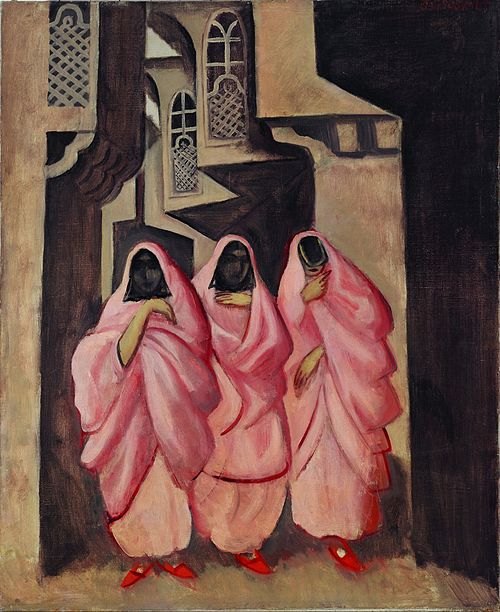

As part of the Mesopotamian Corps, he travelled from what is now Iraq and Iran to the Caucasus. He learnt Persian, kept travel notes in French that he sent to his brother with plans to turn them into a book, and drew extensively. The East fascinated him. He saw harem beauties being ferried along the river, ancient buildings dismantled for the construction of shacks, and a capital fragment supporting the wall of a poor dwelling. In the markets, beggars starved amid abundance, and the locals seemed indifferent to the fate of strangers.

Jāzeps explored this unfamiliar world through his sketches. At the end of the expedition, he fell from a horse, broke his ankle, and underwent an unsuccessful operation; from then on, he walked with a cane.

The artist was discharged from service and went to England for treatment. At that time, his family was in London, where his father served in the diplomatic corps. The closeness and care of his family calmed Jāzeps. He attended medical treatments daily, painted extensively in oils, and began exhibiting his works in art galleries.

In 1919, Jāzeps returned to Riga with his parents and reunited with his circle of artist friends. When Romans Suta and Aleksandra Beļcova, newly married but without a place to live, found themselves in need, he gave them the keys to his apartment on Teātra Boulevard.

His father soon received a new appointment as Latvia’s envoy to Sweden. With his sisters Līna and Margarēta already in diplomatic service, Jāzeps too secured a position- thanks in part to his father’s support- in the diplomatic corps, in his beloved Paris. He felt ready to turn a new page in his life.

In early 1920, not yet 29 years old, Jāzeps fell ill with Spanish flu and died within a week. During the first wave of the epidemic, he had been in the East and escaped it; the second wave, however, caught up with him. He was buried in Paris, but in 1925, in accordance with his family’s wishes, he was reinterred in Riga. With the loss of Jāzeps- at once both patriotic and cosmopolitan- Latvian art suffered an immeasurable blow. It was above all the works created during his Persian period that revealed the extraordinary potential of the artist he could have become.

The Grosvalds family line continued only through his elder sister Mērija Grīnberga, who had a son and a daughter. Her daughter, Mērija Grīnberga the Younger, played a pivotal role after the Second World War in recovering and repatriating his legacy to Latvia.

Leave a comment